2+2[1] 4R is a programming language, one specifically geared toward data analysis.

Like all programming languages, it has certain built-in functions.

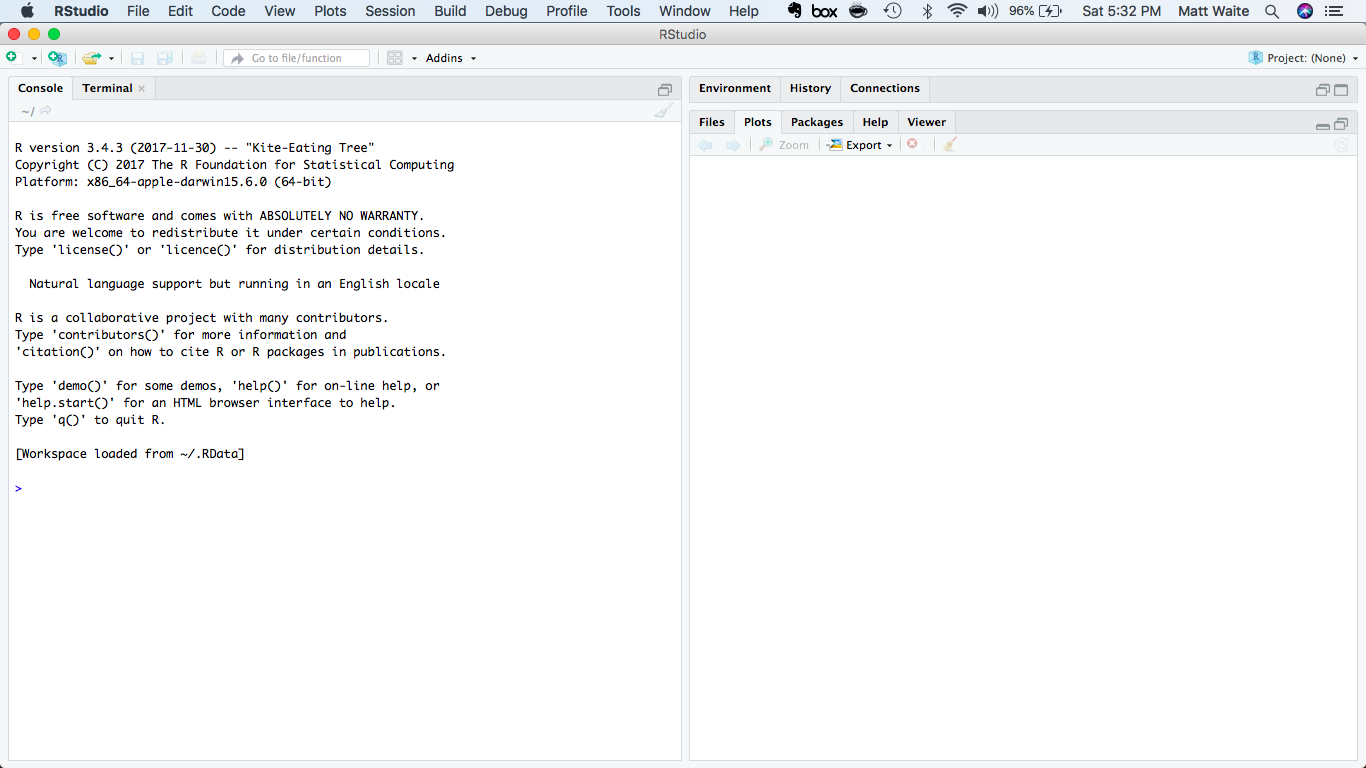

There are many ways you can write and execute R code. The first, and most basic, is the console, shown here as part of a software tool called RStudio (Desktop Open Source Edition) that we’ll be using all semester.

Think of the console like talking directly to the R language engine that’s busy working inside your computer. You use it send R commands, making sure to use the only language it understands, which is R. The R language engine processes those commands, and sends information back to you.

Using the console is direct, but it has some drawbacks and some quirks we’ll get into later. Let’s examine a basic example of how the console works.

If you load up R Studio, type 2+2 into the console and hit enter it will spit out the number 4, as displayed below.

2+2[1] 4It’s not very complex, and you knew the answer before hand, but you get the idea. With R, we can compute things.

We can also store things for later use under a specific name. In programming languages, these are called variables. We can assign things to variables using this left-facing arrow: <-. The <- is a called an assignment operator.

If you load up R studio and type this code in the console…

number <- 2…and then type this code, it will spit out the number 4, as show below.

number * number[1] 4We can have as many variables as we can name. We can even reuse them (but be careful you know you’re doing that or you’ll introduce errors).

If you load up R studio and type this code in the console…

firstnumber <- 1

secondnumber <- 2 …and then type this, it will split out the number 6, as shown below.

(firstnumber + secondnumber) * secondnumber[1] 6We can store anything in a variable. A whole table. A list of numbers. A single word. A whole book. All the books of the 18th century. Variables are really powerful. We’ll explore them at length.

A quick note about the console: After this brief introduction, we won’t spend much time in R Studio actually writing code directly into the console. Instead, we’ll write code in fancied-up text files – interchangably called R Markdown or R Notebooks – as will be explained in the next chapter. But that code we write in those text files will still execute in the console, so it’s good to know how it works.

The real strength of any programming language is the external libraries (often called “packages”) that power it. The base language can do a lot, but it’s the external libraries that solve many specific problems – even making the base language easier to use.

With R, there are hundreds of free, useful libraries that make it easier to do data journalism, created by a community of thousands of R users in multiple fields who contribute to open-source coding projects.

For this class, we’ll make use of several external libraries.

Most of them are part of a collection of libraries bundled into one “metapackage” called the Tidyverse that streamlines tasks like:

To install packages, we use the function install.packages().

You only need to install a library once, the first time you set up a new computer to do data journalism work. You never need to install it again, unless you want to update to a newer version of the package.

To install all of the Tidyverse libraries at once, the function is install.packages('tidyverse'). You can type it directly in the console.

To use the R Markdown files mentioned earlier, we also need to install a Tidyverse-related library that doesn’t load as part of the core Tidyverse package. The package is called, conveniently, rmarkdown. The code to install that is install.packages('rmarkdown')